The Silk Road and Ancient Post Road

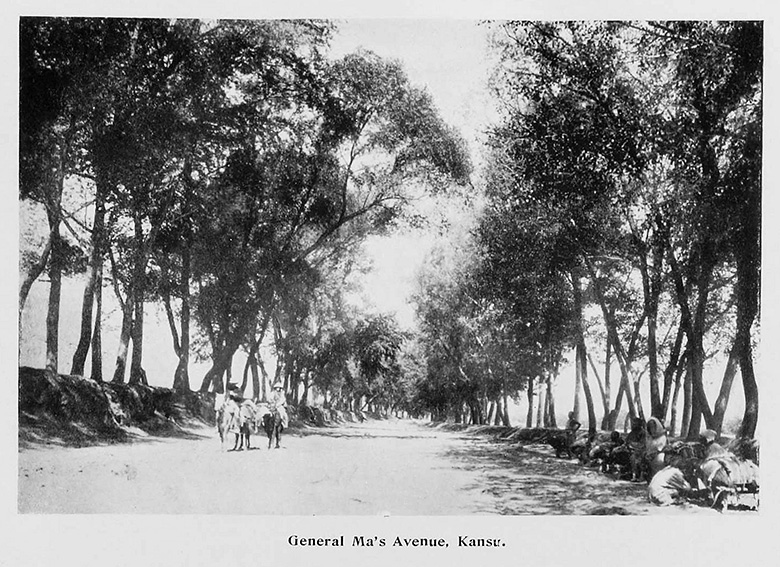

General Ma’s Avenue in Gansu during the late Qing Dynasty. From Through Shên-Kan

The Silk Road and The Ancient Post

Li Ju

The journey Clark and Sowerby undertook from Xi’an to Lanzhou was recorded in chapter VI of Through Shên-Kan. It mentioned they left Xi’an on May 6, 1909 and spent nineteen days traveling. However, forty years later in his autobiography, The Sowerby Saga, Sowerby recalled: “Early in May we were ready to resume our journey to Lan-chou Fu, a journey of some 28 days’ hard travel, in a north-westerly general direction.” Whichever one was accurate, it was a long and arduous trip.

On their way they passed through Xianyang, Liquan, Qianzhou (now Qianxian), Yongshou, Binzhou (now Binxian), Changwu, Jingzhou (now Jingchuan), Pingliang, Jingning, Huining and Anding (now Dingxi), finally arriving in Lanzhou to join up with other expedition members. This journey followed a well-known ancient route which was first trodden during the period of Qin Shi Huang (First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty). When he unified China, work on the “Chi Dao” (ancient royal road) immediately began. Nominally it was for hunting, but the more far-reaching purpose was to demonstrate his power and elicit obedience. In BC 112, Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty made a westerly tour along this road. He crossed Liupan Mountain, and passing Huining arrived at the Zuli River; his journey was recorded in The History of the Han Dynasty.

The eastern section (beyond Pingliang) of this ancient road was established around the time of the Western Zhou Dynasty, the west section during the Han Dynasty, and the complete route finally unified during the Tang Dynasty. As part of the Silk Road, the route thereafter remained essentially unchanged and became the main post road from Shaanxi to Gansu, extending even as far as Xinjiang. In the past it was known as the “Feng Yuan North Road,” and was named as an official road of Lanzhou (Gaolan).

Geographical conditions and social needs led to the creation of this ancient road and the route which Clark and Sowerby walked is in the centre of the east section of the Silk Road. Throughout the Dynasties it was continuously developed and renovated, eventually influencing modern highway construction.

The Silk Road covers a large territorial area and this is just a small fraction. Sections were known by different names during the various dynasties; for example, the east part of the Liupan Mountain was called “a path alongside Jing River”, because of its location. The road climbing over Liupan Mountain was called “Liupan Bird Path” due to the rise and fall of the winding mountain route. Liupan Mountain itself is magnificent, its highest peak, Migang, being 2,942 meters above sea level. The area is precipitous with a variable climate; in summer and autumn it is wet, the mist occasionally reducing visibility to only ten meters; in winter, the snow and ice made travel treacherous and it was not uncommon for carriages and their horses to meet their ends there. (See the sketch of “Liupan Bird Path” (from Annals of Post and Telecommunications in Guyuan Areas ).

Refurbished by Zuo Zongtang (the Governor General of Shaanxi and Gansu between 1871 and 1876) due to the requirements of military strategy, the avenue was named “the post road of Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia” and commonly known as the “Zuo Gong Boulevard.” The width was sufficient for two carts to pass and during the renovation, Zuo Zongtang attached great importance to the planting of trees. They were planted in one or two lines, sometimes four or five rows deep alongside the post road and the view was spectacular, being described as “stretching for many miles, green as army tents.” Throughout history, the avenue played an important role in the economic development of the areas it traversed.

Post Roads played an important role in the economic development, regime consolidation, cultural exchange, and ethnic fusion of ancient society. Post stations were built at intervals along these roads and have a long history. In the Qin Dynasty, called “Ting,” these stations served as a postal collection point, forming a very basic postal delivery system. These facilities provided meals and accommodation for their staff and were also responsible for the management of transport using the roads, however, during the Han Dynasty, their function was widened and they provided accommodation for travelers. By the time of the Tang Dynasty, the name “Yi Zhan” (post station) emerged, their remit exceeding that of previous periods. According to The Yongle Encyclopedia, between the years 1119 and 1125 (during the Song Dynasty), post stations were set up in towns, counties and prefectures to host those requiring their facilities and provide other services as demanded. In the Yuan Dynasty an organization named “Ji Di Pu,” which followed the structure of the previous dynasty, but with a different division of labor, was formed to facilitate the delivery of urgent documents. The name “Yi Zhan” was now pronounced “Zhan Chi” (a Mongolian transliteration).

Due to the constant wars with the northern Mongolians during the Ming Dynasty, additional Great Walls were built and the system of postal delivery was taken seriously. The Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang believed that the name given these post stations, “Zhan Chi,” was inelegant, and he ordered it changed to “Yi,” at the same time restoring the old systems of the Tang and Song Dynasties, which included the provision of water and horses. By the time of the Qing Dynasty, the system had become more refined and possessed an elaborate division of labor. Post Station titles such as “Yi, Zhan, Tang, Tai, Suo and Pu” have virtually the same meaning in different provinces.

Image of a courier. In 1972, at Jiayuguan in Gansu, this painted brick was discovered in an excavated tomb from the Wei-Jin period. It represents a lifelike courier wearing a loose robe and leather boots, riding on a post road with reins in one hand and holding in the other an official dispatch.

By the late Qing Dynasty, post stations had become lax and inefficient and the 2,000-year-old system was re-organized.

A Man on Horseback, exiting a Fortified Structure. Taken by the Clark Expedition. Smithsonian Institution Archives

The postal system had myriad roles. Stations were set up roughly every ten Li (a Chinese unit of length equivalent to 1/2 kilometer). Special couriers were responsible for the delivery of urgent documents, other people for the management of official travel and handling of goods in transit. Some stations in the border areas were manned by soldiers (particularly if the situation was urgent) and responsible for military dispatches. In addition “Suo,” a special organization for official goods delivery and “Pu,” another for general document delivery, each performed their own specialized functions.

The facilities and design of these post stations were mentioned in the book Travel Notes of Northwestern China, written by Pei Jingfu in 1905, “To the west of Pingliang territory, every ten Li, there are three guard houses, one signaling platform and five earth mounds, indicating the distance and location.” (see the sketch p.205) During the period when the central government and ethnic minorities were in fierce competition for political control, these post stations played a role in maintaining order. Beyond their normal function, they were also used as impromptu defensive positions, able to withstand attack. Often, these post stations were linked to garrison camps in strategic passes and these government institutions relied upon each other to form a tight defensive system.

A modern postman on his delivery route.

Although the names of the post stations were different in successive dynasties, they all had the same function and had a common title, “You Yi (or You Chuan). The organization formed two communication structures in the Qing Dynasty: one was horse delivery, based on “Yi,” while foot delivery was concerned with “Pu”. In The Annals of Huining County it was recorded that in 1904 a post station was set up in the county, and postal routes from Huining to Jingning and Huining to Dingxi were opened. The first route was 45 km and was served by two postmen each day on foot. The second route was 30 km and used the same system. The image taken by the Clark expedition is a vivid record of this type of daily postal service.

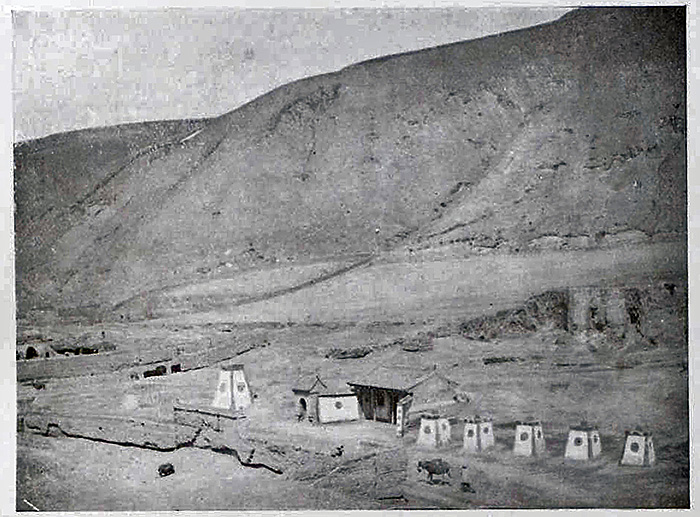

Guard Houses in Gansu. From Through Shên-Kan

The Records of the Postal Service in Gansu state that in 1788 the total length of the main post routes in Gansu was 7,840 Li (nearly 4,000 kilometers), and was divided into three sections covering the east, west and south. The east section commenced in Lanquan Yi in Gansu and ended in Yilu Yi in Shaanxi, covering a total of 2,310 Li.

Today, on this route, many place names recall the ancient post stations with “Ting, Yi, Tang, Suo, Pu” suffixes incorporated into them. Some stations are still in use.

Inspired by the three photos of couriers taken by the Clark expedition, I have collected some historical records and documents recording their circumstances. According to The Records of Posts and Telecommunications in Longde County: Although couriers in the Qing Dynasty were busy running about all the year round, their annual salaries were meager. In 1908 there were thirty-three couriers working in eight delivery stations in Longcheng Yi. Their total pay was 160.73 Liang silver , the average compensation for each courier being less than five Liang a year. Yet their responsibilities were considered gravely important and the slightest transgression could result in the whipping of the postman. Towards the end of the Qing Dynasty, all types of corrupt practices plagued the post stations. It was regarded as “a method of getting rich and a place for reaping unfair gains” by officials at all levels. The courier’s pay was sometimes reduced and their life was hard and unrewarding.

Unlike the scenes recorded during the Han and Tang Dynasties, when envoys, monks, and merchants shuttled along this post road and armies marched with voluminous supplies in a constant stream of humanity, it appears that the road in this photo is deserted, with only some exiled “prisoners” hesitantly posing for the expedition’s camera. Their situation was mentioned in Qi Yunshi’s book, Records of a Long Journey. When serving as an official in the Qing Dynasty, he was convicted by mistake, demoted, and exiled to Ili in Xinjiang. On leaving the capital, the journey took him 170 days and covered ten thousand Li. He recorded the landscapes, historical sites, characters, customs, and ethnic minorities encountered along the way, all later recounted in his book. There was also a similar case, concerning a Lin Zexu, another high ranking official in the Qing Dynasty, former governorgeneral of Shaanxi and Gansu, and twice-appointed imperial minister. He was regarded as a national hero due to his destruction of the opium trade in Guangdong and his resistance to the aggression of western powers. However, he was also demoted and banished to Ili to guard the frontier regions. “He Ge Ji Cheng,① A Record of the Exile’s Journey” are his notes recording what he had observed on his way to exile. Later, Pei Jingfu, an exiled official who also traveled this road wrote a similar book, “Travel Notes of Northwestern China”.

When Clark and Sowerby walked this road, they were observers of some of these “exiles.” The shackled prisoners were dressed in tattered clothes, and three of them were also bound by wooden chains. They carried crude weapons on their way to exile. Since the five prisoners were photographed in two slightly different positions, we can guess Clark and Sowerby arranged their poses. The long shadows in the bottom right hand corner of the first photograph suggest others were watching also.

Clark and Sowerby took many photos during their trip. Some are without clear indications of their location. However, this omission does not affect the sense of time and place, and contemporary readers can appreciate these vivid images of a different time.

Exiles. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

By the road on this cliff face to the west of Dafo Temple in Binxian the remains of a large painted slogan can be seen. It was written by the Northwest Road Transport Administration in 1940 and reads: “We drivers must have a spirit identical to those frontier soldiers who shed their blood in tough battles”, reflecting the situation of those transporting troops and equipment during the Anti-Japanese War.

① “He Ge Ji Cheng” (《荷戈纪程》) - “He” means carrying and “Ge” is the name of an ancient weapon. “He Ge” refers to guarding the frontier with weapons, and became synonymous with dismissal and exile.

[ Top ]